The following contribution has been previously published in one of my earlier catalogues. It attracted great attention, as documented by a lengthy quote in “La Stampa” on the 3rd of March 2012 (see reproduction). I would like to thank the author Prof. Dr. C. Wolfgang Müller for facilitating access to it and his kind permission to re-print it and. I would also like to thank “La Stampa” for a copy of this extract and last but not least, Dr. Cristiane Müller-Wichmann for her helpful advice.

Carin Grudda

ON REGAINING LOCALITY

Prof. Dr. Wolfgang Müller to Carin Grudda

To a great extend during the Italian Middle Ages fine art was regarded as crafts. Painters and sculptors were considered to be craftsmen. Which was mirrored by their status and wages. The church as their employer determined the subject and narrative. They were expected to copy the masters. Individual innovation was not required. The location for the works of art was designated before conception. Everything was already predetermined before conception with frescoes and altar paintings. The painter could just about add the patron into a corner.

The Italian Renaissance brought a gradual emancipation of the fine arts from the spirit of crafts and the dictate of a direct commission. This liberation process changed the craftsman into an artist. It also released the work of art from its local context. Individual buyers and later on collectors replaced the contractor – formerly a personally acquainted patron.

In the Netherlands, the hub of European over-seas trade, a new audience evolved, which did not commission works of art anymore but bought collector’s pieces from art dealers. These were investments and status symbols. The art dealers worked as subcontractors. Paintings and sculptures travelled from place to place and later as the spoils of wars within the course of the centuries around the globe. Excavations to salvage the Greco-Roman Antique did the rest. The Babylonian procession road from the time of Nebukadnezar II (604 – 562 BC) was removed from its local context and rebuilt inside the Berlin Pergamon Museum during the 20th century in a neutral exhibition environment, then repeatedly taken down and reconstructed during the course of World War II. Generally speaking: It had been removed from the time and space of its conception and displayed as a consumable aesthetic commodity.

One hundred years after the Pergamon Museum opened its doors for the first time, a split of dealing with time and space in relationship to contemporary works of art seems to be apparent, at least in middle Europe.

On the one hand, the global marketing of its products is being pushed to the extreme, on the other, there seems to be a recollection on the aesthetic qualities of the local as a living and working environment. Artists seemed to have settled to fixed locations again. They no longer produce for an unknown, worldwide audience. They say, that they live and work in city X and for example create a fairytale cat for town Z as a ride for children. Committed mayors of new satellite towns at the margins of urban centres try to create a recognisable face for their drawing board settlements. They want to regain the aesthetic images imprinted on the memory of our grandparents which is long lost, because city and country life, working and living, money-making and home-making are separated by a complicated dissociation processes and the childhood dreams of our grandparents cannot be regained by the game consoles of the grandchildren.

The connection of childhood dreams and the modern life influenced and changed by the innovations of the 21st century may be a challenging task for contemporary artists, because they take a look ahead but also take on the challenge to turn a glance back into a time in which, for them, a story began, which is as infinite as the search for an uncertain future.

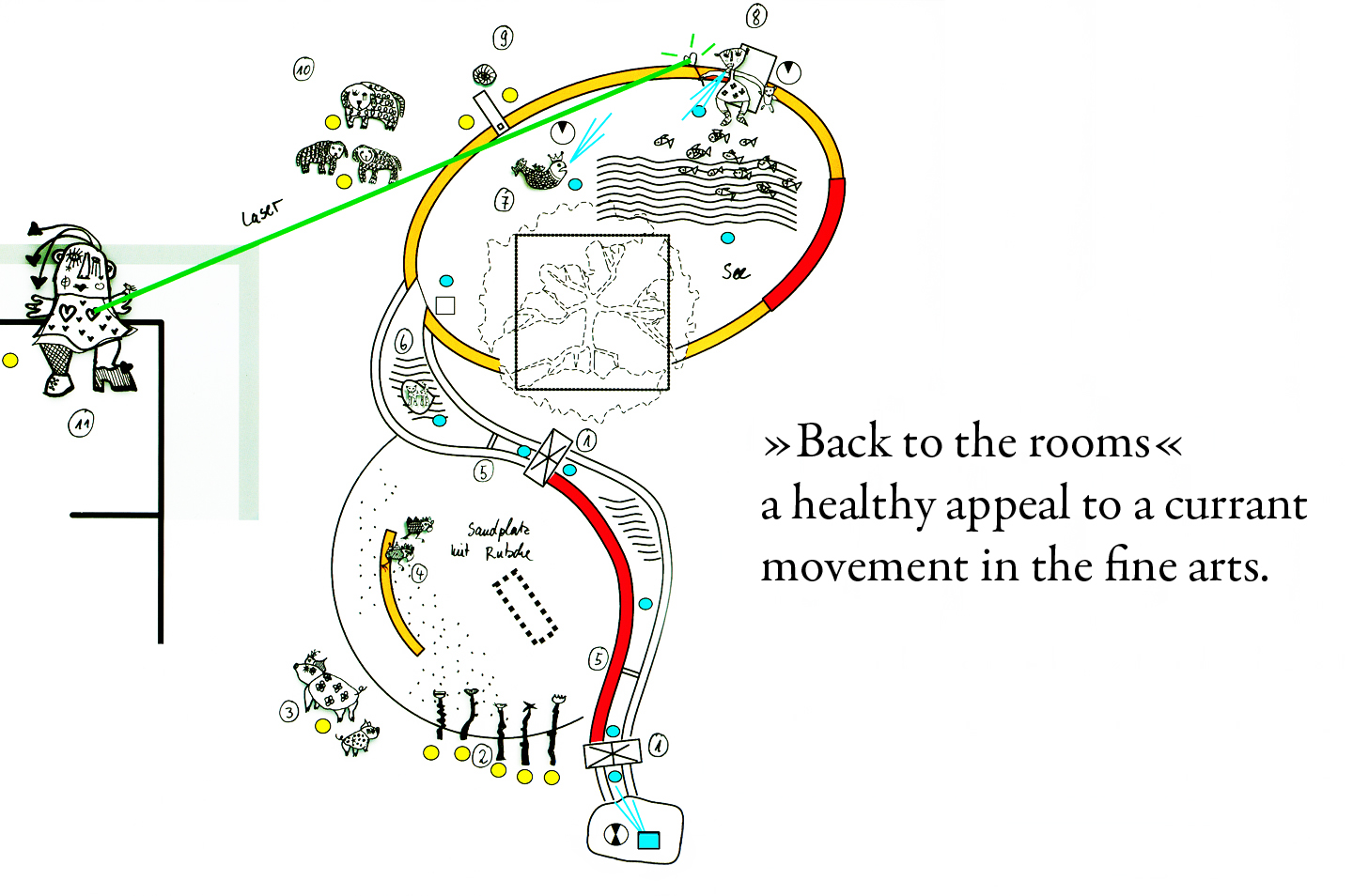

“Back to the roots” was not only the healing call in psychoanalysis. “Back to the rooms” could be a healthy appeal to a current movement in the fine arts, which turned its back on the dichotomy of “introspection” and “external perception” looks for a connection between the childhood home and the outside world in later life, between the vicinity of the parental home and the distant place where we all have to attempt to find a new home.

There seems to be artists like Carin Grudda who are working hard on this task – and give hope.

Prof. Dr. Wolfgang Müller

The author:

C. Wolfgang Müller; Dr. phil., Dr. h.c., former professor at the Technical University of Berlin is a doyen for social and educational sciences in Germany at university level and specialises on community organisation and development since his studies in the USA in the mid-1960s. He has countless publications, awards and honorary posts in this field.